The Mughal Empire, spanning over three centuries from 1526 to 1857, was one of the most powerful and influential empires in the history of the Indian subcontinent. Founded by Babur, a descendant of Timur and Genghis Khan, the Mughals established a dynasty that would come to be known for its architectural wonders, cultural synthesis, administrative innovations, and the blending of Persian and Indian traditions. The empire’s legacy continues to shape modern India, particularly in the areas of art, architecture, language, and governance.

Babur: The Genesis of Mughal Rule

Zahir-ud-din Muhammad Babur was born in 1483 in the Fergana Valley, which lies in present-day Uzbekistan. As a descendant of Timur on his father’s side and Genghis Khan on his mother’s, Babur inherited both the legacy of great conquerors and the ambition to expand his rule. Despite several setbacks in Central Asia, Babur’s determination led him to look towards India, where the political landscape was fragmented and ripe for conquest.

Babur’s journey to establishing the Mughal Empire began with his victory at the First Battle of Panipat in 1526. Facing the Sultan of Delhi, Ibrahim Lodi, Babur’s forces were significantly outnumbered, but his innovative use of field artillery, combined with tactical brilliance, led to a decisive victory. This battle not only marked the end of the Delhi Sultanate but also laid the foundation for Mughal rule in India.

After his initial success, Babur faced challenges from various regional powers, including the Rajputs and the Afghan chieftains. In 1527, he defeated Rana Sanga of Mewar at the Battle of Khanwa, further solidifying his control over northern India. Babur’s military campaigns were complemented by his administrative acumen, as he worked to establish order and stability in the newly conquered territories.

Despite his short reign, which ended with his death in 1530, Babur left behind a robust framework for governance and a rich cultural legacy. His autobiography, the **Baburnama**, is a unique literary work that provides insights into his life, thoughts, and the early years of the Mughal Empire. The Baburnama is not just a chronicle of events but also a reflection of Babur’s keen interest in nature, poetry, and the arts.

Humayun: Trials, Exile, and the Reclamation of the Empire

Upon Babur’s death, his son Nasir-ud-din Muhammad Humayun ascended the throne in 1530. However, Humayun’s reign was fraught with difficulties from the outset. Unlike his father, Humayun struggled to maintain control over the empire, facing formidable opposition from Afghan rulers, most notably Sher Shah Suri. In 1540, after a series of defeats, Humayun was forced into exile, and the Mughal Empire temporarily collapsed.

During his exile, Humayun sought refuge in Persia, where he was warmly received by Shah Tahmasp I of the Safavid dynasty. This period of exile proved to be formative for Humayun, as he adopted several Persian customs and administrative practices that would later influence the Mughal court. After nearly 15 years of exile, Humayun, with Persian military support, managed to reclaim his throne in 1555 following the decline of the Suri dynasty.

Humayun’s return to power was short-lived, as he died in 1556 after a tragic accident. Nevertheless, his efforts to restore the Mughal Empire laid the groundwork for its resurgence under his son, Akbar. Humayun’s architectural contributions, such as the construction of his tomb in Delhi, exemplify the synthesis of Persian and Indian styles that would come to define Mughal architecture.

Akbar the Great: Architect of the Mughal Empire’s Golden Age

Jalal-ud-din Muhammad Akbar, born in 1542, ascended the Mughal throne at the tender age of 13 after Humayun’s death. Akbar’s reign, lasting from 1556 to 1605, is often regarded as the zenith of the Mughal Empire, marked by extensive territorial expansion, administrative innovation, and the promotion of cultural and religious synthesis.

Military Conquests and the Expansion of the Empire

Akbar’s early years as emperor were dominated by the regency of Bairam Khan, who played a crucial role in securing the Mughal throne by defeating Hemu at the Second Battle of Panipat in 1556. This victory not only solidified Akbar’s position but also marked the beginning of a series of military campaigns that would expand the Mughal Empire across the Indian subcontinent.

Throughout his reign, Akbar employed a combination of diplomacy, marriage alliances, and military might to bring various regions under Mughal control. He forged alliances with powerful Rajput clans by marrying Rajput princesses, which helped to secure their loyalty and integrate them into the Mughal administration. Akbar’s conquests extended the empire’s boundaries from the Himalayas in the north to the Deccan Plateau in the south, and from Afghanistan in the west to Bengal in the east.

One of Akbar’s most significant military achievements was the conquest of Gujarat in 1573, which secured the empire’s control over the lucrative trade routes and ports of western India. His campaigns in Rajasthan, particularly the siege of Chittorgarh in 1568, were instrumental in bringing the Rajput kingdoms under Mughal suzerainty. In the latter part of his reign, Akbar turned his attention to the Deccan, where he successfully annexed the Sultanates of Ahmednagar, Berar, and Khandesh.

Administrative Reforms and the Consolidation of Power

Akbar’s administrative reforms were key to the consolidation and long-term stability of the Mughal Empire. He implemented a centralized system of governance that balanced the need for imperial control with the autonomy of regional administrators. The **Mansabdari System**, introduced by Akbar, was a hierarchical administrative framework that classified military and civil officials based on their rank or **mansab**. This system ensured that the empire’s vast bureaucracy and military were loyal to the emperor, as the mansabdars’ income and status were directly tied to their service to the state.

Akbar’s reforms extended to the revenue system as well. He introduced the **Zabt** system, a standardized method of land revenue assessment and collection. This system, designed by Raja Todar Mal, involved detailed surveys of agricultural land and the classification of land based on its fertility. Revenue was collected in cash rather than in kind, which helped to streamline the empire’s finances and reduce corruption. The Zabt system also provided peasants with a degree of protection, as it established a fixed revenue demand based on the productivity of their land.

Akbar’s administration was marked by a spirit of inclusivity and tolerance. He abolished the jizya, a tax on non-Muslims, and appointed individuals from various religious and ethnic backgrounds to key positions within the government. This policy of religious tolerance was a cornerstone of Akbar’s rule, as he sought to integrate the diverse populations of his empire into a cohesive and unified state.

Religious Tolerance and Cultural Synthesis

Akbar’s policy of religious tolerance extended beyond mere administrative pragmatism; it was rooted in his personal philosophy and spiritual outlook. He was deeply interested in exploring the commonalities between different religions and fostering an environment of mutual respect and understanding. In 1575, Akbar established the **Ibadat Khana** (House of Worship) at his capital in Fatehpur Sikri, where scholars and theologians from various religious traditions, including Islam, Hinduism, Jainism, Zoroastrianism, and Christianity, engaged in debates and discussions.

These discussions led Akbar to develop a syncretic religious doctrine known as **Din-i-Ilahi** or the “Religion of God.” Din-i-Ilahi was an attempt to create a spiritual framework that transcended the boundaries of individual religions and promoted the idea of universal peace and harmony. Although Din-i-Ilahi did not gain widespread acceptance, it reflected Akbar’s vision of a unified and tolerant empire.

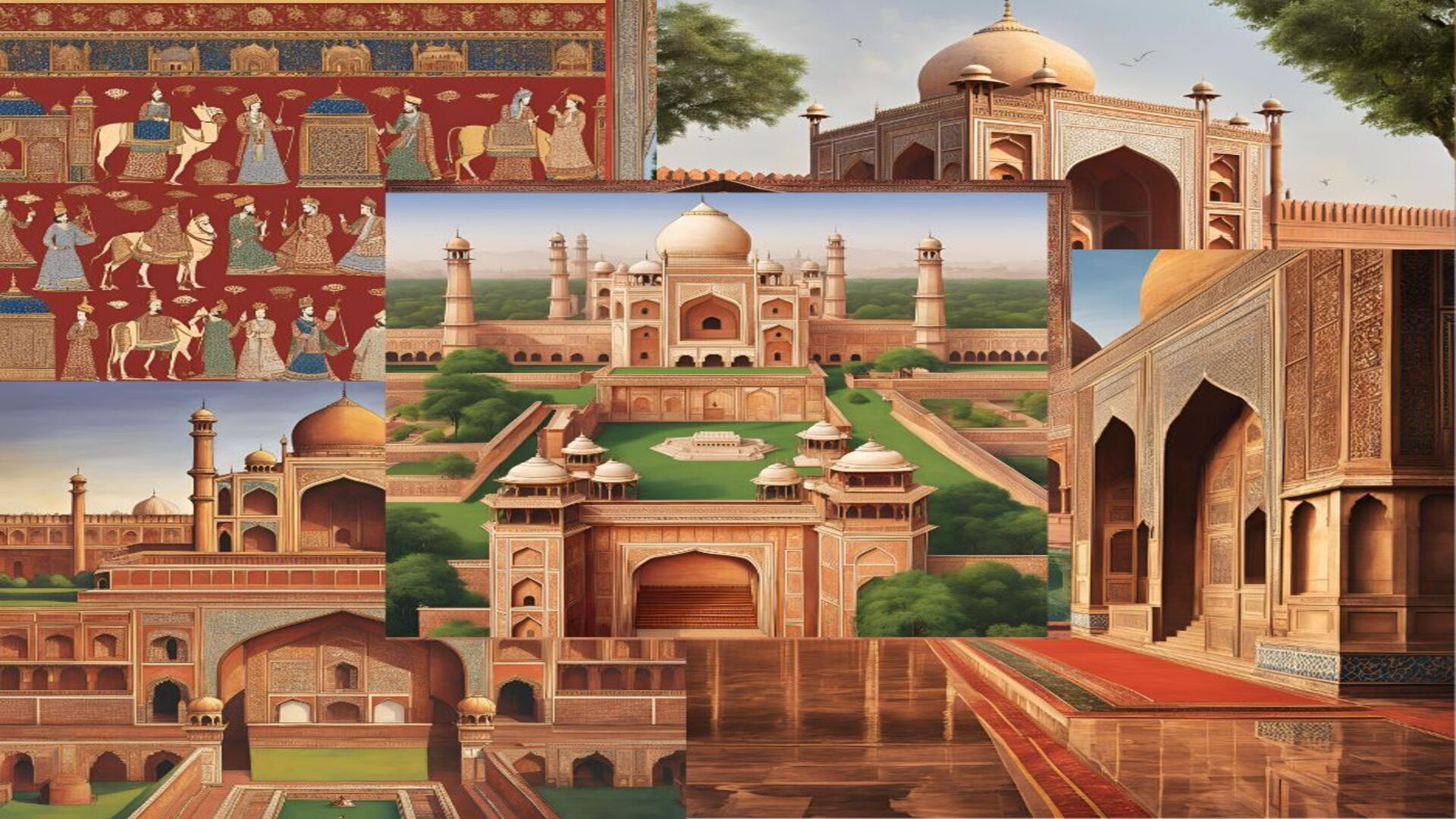

Akbar’s patronage of the arts and culture also played a crucial role in the synthesis of Persian, Indian, and Central Asian traditions. His court became a center of artistic and intellectual activity, attracting poets, musicians, painters, and scholars from across the empire and beyond. The Mughal school of painting, which flourished under Akbar, combined Persian techniques with Indian themes, resulting in a distinctive style characterized by vivid colors, intricate details, and a focus on naturalism.

In architecture, Akbar’s reign saw the construction of several iconic structures that blended Persian, Islamic, and Indian architectural elements. The city of Fatehpur Sikri, built as Akbar’s capital, is a testament to this architectural synthesis, with its grand palaces, mosques, and public buildings reflecting the emperor’s vision of a culturally integrated empire.

Jahangir: The Empire at its Zenith and the Blossoming of the Arts

Following Akbar’s death in 1605, his son Nur-ud-din Muhammad Jahangir ascended the throne. Jahangir’s reign, lasting from 1605 to 1627, is often viewed as a period of consolidation and cultural flourishing. While Jahangir continued many of Akbar’s policies, his rule was marked by a greater focus on the arts, particularly painting, and a deep interest in nature and the environment.

Political Stability and the Role of Nur Jahan

Jahangir’s reign was characterized by political stability, largely due to the strong administrative foundations laid by Akbar. Jahangir maintained the Mansabdari and Zabt systems, ensuring continuity in governance. However, his reign was also notable for the significant influence of

his wife, Nur Jahan, who became one of the most powerful women in Mughal history.

Nur Jahan, originally named Mehr-un-Nissa, was an astute politician and administrator. She effectively managed the affairs of the state, issuing royal decrees, minting coins in her name, and even deciding matters of succession. Her influence extended to the court, where she promoted Persian culture and patronized the arts. Nur Jahan’s political acumen and her ability to navigate the complex dynamics of the Mughal court ensured the stability of the empire during Jahangir’s reign.

Jahangir’s rule was also marked by his interest in justice and governance. He established a “Chain of Justice” outside his palace, allowing subjects to directly appeal to the emperor for redress. This symbolic gesture underscored Jahangir’s commitment to justice and his desire to maintain a personal connection with his subjects.

Artistic Patronage and Cultural Flourishing

Jahangir was a passionate patron of the arts, and his reign is often considered the golden age of Mughal painting. Under his patronage, the Mughal miniature painting tradition reached new heights, characterized by a keen attention to detail, realism, and a refined aesthetic sensibility. Jahangir’s interest in nature was reflected in the art of his time, with many paintings depicting animals, birds, and flowers with remarkable precision.

Jahangir’s court was a vibrant cultural hub, attracting artists, poets, and scholars from across the empire and beyond. The emperor himself was a connoisseur of art, and his personal diaries, known as the **Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri**, provide a detailed account of his artistic tastes and his interactions with artists. These diaries also reveal Jahangir’s fascination with European art and his collection of European paintings and prints, which influenced the development of Mughal art.

In addition to painting, Jahangir’s reign saw significant developments in architecture. Although Jahangir did not commission as many grand structures as his predecessors, the buildings constructed during his reign, such as the **Tomb of Itimad-ud-Daulah** in Agra, exemplify the delicate and refined aesthetic that characterized Mughal architecture. This tomb, often referred to as the “Baby Taj,” is notable for its intricate marble inlay work and its use of white marble, which would later become a hallmark of Mughal architecture.

Jahangir’s reign also witnessed the flourishing of literature and the sciences. The emperor’s interest in botany and zoology led to the documentation of various species of plants and animals, often accompanied by detailed illustrations. This emphasis on natural history was part of a broader Mughal tradition of curiosity and exploration, which had been encouraged by Akbar and continued under Jahangir.

Shah Jahan: The Pinnacle of Mughal Architecture and the Strains of Power

Jahangir was succeeded by his son Shahab-ud-din Muhammad Khurram, better known as Shah Jahan, who ruled from 1628 to 1658. Shah Jahan’s reign is often associated with the pinnacle of Mughal architecture, exemplified by the construction of the **Taj Mahal**, one of the most iconic and enduring symbols of the Mughal Empire. However, his reign was also marked by increasing centralization of power and the seeds of the empire’s eventual decline.

Architectural Grandeur: The Legacy of Shah Jahan

Shah Jahan’s reign is most renowned for its architectural achievements, which reflect the emperor’s love of beauty and his desire to leave a lasting legacy. The Taj Mahal, built as a mausoleum for his beloved wife Mumtaz Mahal, is the most famous of these structures. Completed in 1653, the Taj Mahal is a masterpiece of Mughal architecture, combining elements of Persian, Indian, and Islamic design. Its white marble facade, intricate inlay work, and symmetrical gardens have made it one of the most celebrated buildings in the world.

In addition to the Taj Mahal, Shah Jahan commissioned the construction of several other significant architectural works. The **Red Fort** in Delhi, with its massive walls, grand gates, and ornate palaces, served as the imperial residence and a symbol of Mughal power. The **Jama Masjid** in Delhi, one of the largest mosques in India, is another example of Shah Jahan’s architectural vision, characterized by its imposing scale and harmonious proportions.

Shah Jahan’s architectural projects extended to the city of **Shahjahanabad** (modern-day Old Delhi), which he founded as the new Mughal capital. The city was designed as a showcase of Mughal grandeur, with wide boulevards, bustling markets, and magnificent buildings. Shah Jahan’s patronage of architecture left a lasting imprint on the Indian landscape, with his buildings continuing to inspire awe and admiration to this day.

Centralization and the Challenges of Governance

While Shah Jahan’s reign was marked by architectural brilliance, it was also a period of increasing centralization of power. Shah Jahan sought to strengthen the authority of the emperor and consolidate control over the empire’s vast territories. This centralization was achieved through a combination of administrative reforms, military campaigns, and the suppression of dissent.

Shah Jahan’s efforts to centralize power were reflected in his relationship with the nobility and the military. He sought to curtail the influence of powerful nobles by appointing loyalists to key positions and by restructuring the **Mansabdari System** to ensure greater control over the empire’s military forces. Shah Jahan also expanded the empire’s standing army, which placed a significant strain on the empire’s finances.

Despite these efforts, Shah Jahan’s reign was not without challenges. The cost of his ambitious building projects, combined with the expense of maintaining a large military, led to financial difficulties. Additionally, Shah Jahan’s attempts to suppress regional rebellions and expand the empire’s territories in the Deccan and Central Asia proved costly and, in some cases, unsuccessful. These challenges, coupled with growing tensions within the royal family, foreshadowed the difficulties that would confront the Mughal Empire in the years to come.

Aurangzeb: Expansion, Orthodoxy, and the Decline of the Empire

Shah Jahan’s reign came to a turbulent end in 1658 when his son Aurangzeb deposed him in a bitter struggle for the throne. Aurangzeb, who ruled from 1658 to 1707, was the last of the great Mughal emperors. His reign was characterized by significant territorial expansion, a return to Islamic orthodoxy, and a series of policies that would ultimately contribute to the empire’s decline.

Expansion and Military Campaigns

Aurangzeb’s reign saw the Mughal Empire reach its greatest territorial extent, stretching from the Hindu Kush in the northwest to the Carnatic region in the south. Aurangzeb was a tireless military commander, leading numerous campaigns to subdue regional kingdoms and expand the empire’s borders.

Aurangzeb’s most significant military achievement was the conquest of the Deccan Sultanates, which brought much of southern India under Mughal control. The prolonged and costly campaigns in the Deccan, however, drained the empire’s resources and weakened its administrative structure. Aurangzeb’s expansionist policies also led to increased resistance from regional powers, such as the Marathas, who waged a relentless guerrilla war against the Mughal forces.

Despite his military successes, Aurangzeb’s expansionist policies created a vast and unwieldy empire that was difficult to govern. The constant warfare and the need to maintain a large standing army placed immense strain on the empire’s finances, leading to widespread discontent and unrest.

Religious Policies and the Shift Towards Orthodoxy

Aurangzeb’s reign marked a departure from the religious tolerance that had characterized the rule of his predecessors. A devout Sunni Muslim, Aurangzeb sought to impose Islamic orthodoxy throughout the empire. He reimposed the **jizya** on non-Muslims, banned the construction of new Hindu temples, and destroyed several existing temples. Aurangzeb also enforced stricter adherence to Islamic law, prohibiting practices that he viewed as un-Islamic, such as music and dance at court.

These policies alienated large segments of the population, particularly the Hindu majority, and led to increased resistance to Mughal rule. The Marathas, under the leadership of Shivaji, emerged as a formidable force in the Deccan, challenging Mughal authority and waging a protracted struggle for independence. Aurangzeb’s religious policies also created tensions within the empire’s administration, as many Hindu nobles and officials, who had been integral to the Mughal state, felt marginalized and disillusioned.

Aurangzeb’s orthodox policies extended to the suppression of Sufi practices and the persecution of religious minorities, such as Sikhs and Jains. His strict interpretation of Islam and his efforts to enforce religious conformity alienated not only non-Muslims but also Muslims who adhered to different interpretations of the faith.

The Decline of the Empire

Aurangzeb’s death in 1707 marked the beginning of the decline of the Mughal Empire. The vast and diverse empire that Aurangzeb had built proved too difficult to govern, and the succession struggles that followed his death further weakened the central authority. The empire faced internal rebellions, such as the Sikh uprising in Punjab and the Rajput revolt in Rajasthan, as well as external threats from emerging powers like the Marathas and the British East India Company.

The empire’s financial difficulties were exacerbated by the costly military campaigns and the decline in agricultural productivity. The weakening of central authority led to the rise of regional governors and warlords who carved out their own autonomous states, further eroding the empire’s territorial integrity.

By the mid-18th century, the Mughal Empire had been reduced to a shadow of its former self, with the emperor confined to the Red Fort in Delhi and wielding little

A.B.M. Abir

A.B.M. Abir