Women Can Cast Votes, But Cannot Stand as Candidates!

- Update Time : 08:31:59 am, Wednesday, 4 February 2026

- / 40 Time View

The letter “X” in English has always carried a sense of mystery. It can mean unknown, former, adult, or many other things. Lately, the social media platform X has become a major topic of discussion, debate, and controversy in Bangladesh. The heat from smartphones, tablets, laptops, and desktops has spilled into real life, starting with an incident on Saturday afternoon.

A post appeared in English on the verified X handle of Shafiqul Rahman, the Amir of Bangladesh Jamaat-e-Islami. Translated into Bengali, a portion read: “We believe that when women are encouraged to leave their homes under the guise of modernity, they face exploitation, moral decay, and insecurity. This is nothing else but another form of prostitution.”

Jamaat has claimed that their Amir’s account was hacked through a well-planned conspiracy. Meanwhile, the BNP has questioned how credible it is to claim the account was recovered shortly after the hack.

In Bangladesh’s current political climate, verifying truth and falsehood has become secondary to using social media algorithms to shape narratives. After three one-sided elections and a series of flawed voting processes, a tense election environment has emerged. Ethnic and religious minority voters continue to experience fear and uncertainty. Even though roughly 9.5% of voters have cast ballots, many remain unsure whether participating or abstaining is the better choice.

A recent discussion by the Center for Governance Studies (CGS) noted that minority voters could be a decisive factor in around 80 constituencies. Yet, among the 2,017 candidates in the upcoming election—across parties and independents—only about 80 come from minority communities, with 12 independents. Out of 51 participating political parties, only 22 fielded minority candidates. The CPB nominated 17, BNP 6, and Jamaat just 1.

While religious and ethnic minorities are numerically smaller, women constitute a majority population in the country, outnumbering men by 1.6 million. Despite this, the latest voter lists show 2 million fewer female voters than males, and there are only 78 female candidates in the election—61 party-affiliated and 17 independents. Thirty parties, including Jamaat, fielded no female candidates, while BNP nominated 10. Other leftist parties like CPB and BASAD included a few women candidates.

Although the 2014 people’s uprising promised inclusion and pluralism, over the past 17 months, women have been the most marginalized group. The electoral environment remains hostile toward women, continuing the pattern of the past year and a half. Women have faced online and offline harassment, their public space restricted, and targeted hate campaigns on social media. Very few political parties have protested against this dual violence—both online and in the real world.

Even though Bangladesh has had female prime ministers in its two largest parties for decades, women’s political participation remains largely symbolic. In no national election has the share of female candidates exceeded 5%. Those women who have been directly elected are mostly exceptions, often winning seats allocated via quotas for relatives—wives, daughters, or mothers. Reserved seats for women exist primarily as formal representation.

During the caretaker government, the reform commission allegedly made decisions about women without including female representation. After extensive negotiation, 26 political parties and alliances agreed to nominate women in at least 5% of constituencies, signing this commitment in July before entering the elections. Yet political promises remain hollow; parties can ignore them once in power, shaping narratives to justify their actions.

This year, parties have nominated women in only 3.4% of constituencies. Many of these women are selected through family connections rather than independent political merit. Jamaat has not nominated any female candidates. In a recent interview with Al Jazeera, Jamaat Amir Shafiqul Rahman stated that no women could hold top positions in his party, though preparations for nominating women are reportedly underway.

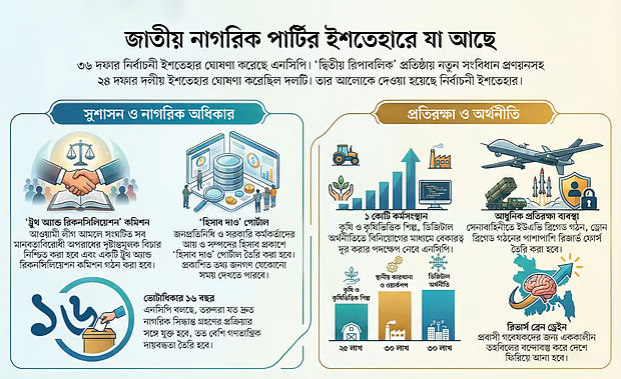

Amid political maneuvering, moderate positions, and alliances with Islamist parties, women candidates face continuous challenges. For instance, NCP initially listed 14 female candidates out of 125, but after allying with Jamaat, several women resigned from political roles, leaving only two women running under NCP this election.

Thousands of female activists from Jamaat have been campaigning for months, visiting homes to encourage women voters, despite facing resistance, threats, and harassment. The issue of women activists being obstructed has become a central concern for Jamaat leadership.

BNP female activists are also campaigning across constituencies, and in some areas, candidates’ wives are participating to engage voters. However, incidents continue where male leaders or opposing candidates display disrespectful behavior toward women candidates. For example, in one televised program, an Islamic Movement candidate refused to sit alongside a female BASAD candidate.

Digital platforms have amplified hostility toward women, with online hate campaigns becoming a political tool. Misogynistic campaigns are increasingly used as weapons to sway voters, similar to tactics observed in India and the U.S.

While political leaders publicly claim to support women’s rights and dignity, the persistent use of bot networks to promote anti-women narratives exposes the contradiction. Over the past 17 months, women have been further marginalized in public and political spaces. Social media campaigns have narrowed their visibility and targeted them for harassment, continuing a longstanding pattern.

At the same time, parties that deny women candidacy are paradoxically using them as a tool to attract votes. This reflects a deep-seated political double standard.